Andrew Gillen

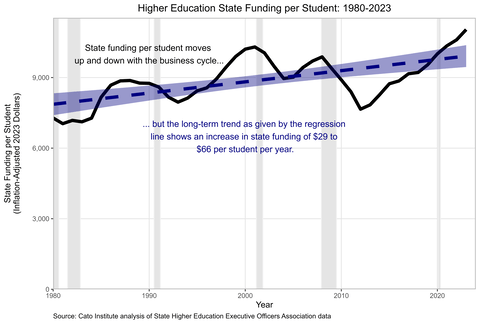

You can’t go long reading about higher education before coming across a lament about cuts in state funding for higher education, often called state disinvestment. There’s just one problem—as documented in a new Cato briefing paper, states have been increasing funding over the past few decades, not cutting it. The figure below shows inflation-adjusted state funding per student over the last 43 years (the black line) as well as the long-term trend as given by the regression line (the blue line). The long-term trend line shows that state funding increases by $48 (±$18) per student per year. This increase in funding over time means that state disinvestment is a myth.

But while state disinvestment at the national level is a myth, there is some variation by state. The figure below shows the estimate of the long-term trend by state. There is statistically significant evidence that 24 states have increased funding over time (green), that 6 have decreased funding over time (red), and that there is no convincing upward or downward trend in 20 states (grey). So while there are six states for which state disinvestment is real, for each one of those, there are four states that have increased funding and more than three states that have seen essentially no change in funding over time.

The main damage caused by the myth of state disinvestment is a misdiagnosis of why tuition has increased. State disinvestment provides a plausible reason for higher tuition—as states cut funding for colleges, the colleges have no choice but to raise tuition to fill the financing hole.

But there are two main problems with this argument. First, there is no state disinvestment since states have been increasing funding, not cutting it. This implies that colleges should have been cutting tuition, not raising it.

The second problem is that it assumes a $1‑to-$1 relationship between changes in state funding and changes in tuition with tuition rising by $1 for every $1 cut in state funding. But the data contradict this assumption. The figure below shows the change in state funding and change in tuition revenue per student by year. If the 1‑for‑1 relationship were true, then each year should fall along the red line, but most years do not. The actual relationship is given by the blue regression line and shows that a $1 cut in state funding is correlated with an increase in tuition from $0.03 to $0.29, not $1.

The new briefing paper goes into more detail on these and related topics (including a possible beneficial change in the trends in tuition). Remember, state disinvestment in higher education is a myth, and it doesn’t explain increases in tuition.